In preparation for Restoration Fellowship’s Theological Conference, I began work on a research paper to explain how the process of Bible translation works. While putting this paper together, I kept coming across important topics that I felt uncomfortable excluding. Whenever possible I prioritized brevity over thoroughness and still the “paper” grew beyond the 10 page maximum until it was 60 pages long. At several key moments early on, I thought about reducing the scope of the essay to one narrow subject, but felt strongly that what people need is an overview of the whole process rather than a narrow treatment of an isolated part. As it turned out, the April conference succumbed to COVID-19 prohibitions, which emboldened my expansion by giving me another month to work on the project. If the postponed conference occurs in late July, I hope to present a modified version of the section on the King James Version.

Regardless of what happens with this year’s TheoCon, I plan to use this research as the basis for a series of lectures (both video and audio versions) aimed at the common person. I suspect many Restitutio fans will enjoy the somewhat technical language below while others will prefer the more accessible lecture version.

I especially want to thank those who donated to Restitutio over the past couple of months, without whose support I could not have acquired the resources necessary for a project of this breadth. Additional, I’m indebted to Dr. Jerry Wierwille not only for access to his considerable collection of books on translation philosophy and textual criticism, but also for reading the draft and offering many helpful criticisms.

You can read the paper below, download the pdf, or read it on academia.edu.

Bible Translation Sources and Theory

By Sean Finnegan

Published May 9, 2020

Restitutio.org

Presented at the 29th Theological Conference

Sponsored by Restoration Fellowship

July 31, 2020

Contents

2 The Text of the Old Testament

2.1 Hebrew Manuscripts

2.2 Hebrew Critical Text

2.3 Redactions

3 The Text of the New Testament

3.1 Greek Manuscripts

3.2 Greek Critical Text

4 Translation Approaches

4.1 Formal Equivalence (Word for Word)

4.2 Dynamic Equivalence (Thought for Thought)

4.3 Formal and Dynamic Equivalence Styles Illustrated

5 Translation Decisions

5.1 Units of Measurement

5.2 Idioms

5.3 Gender Inclusiveness

5.4 Editorial Helps

5.5 Lexicography

5.6 English Vocabulary

5.7 God’s Name

6 Two Enduring Corruptions

6.1 The Ending of Mark (Mark 16.9-20)

6.2 The Adulteress Woman (John 7.53-8.11)

7 The King James Version

7.1 Flawed Manuscripts and Archaic English

7.2 Who Was Manifested? (1 Timothy 3.16)

7.3 Three that Testify (1 John 5.7-8)

7.4 A Final Word about the King James Version

8 The Message Bible

8.1 Old Testament Analysis

8.2 New Testament Analysis

8.3 A Final Word about the Message Bible

8.4 Evaluating the Passion Translation

9 Bias in Committee Translations

9.1 Reasons for Bias in Popular Translations

9.2 God’s Form or God’s Nature? (Philippians 2.6-7)

9.3 Bow or Worship? (Proskuneo)

9.4 Firstborn of or Firstborn over? (Colossians 1.15)

9.5 Did Jesus Claim To Be “I AM?” (John 8.58)

9.6 Spirit Who or Spirit Which?

Appendix 1: Abbreviations

Appendix 2: A Case against Majority Text Priority

1 Introduction

In preparation for this research project, I visited my local Barnes & Noble and perused their well-endowed Bible section. While gazing at the potpourri of marketing gimmicks enticing customers to buy this or that Bible, my eye fell upon a little pamphlet designed to guide purchasers. This shiny brochure self-identified as “A comprehensive guide to the most popular Bible translations & how to find the right Bible for your needs.”[1] In light of the many hours of research I have poured into understanding manuscript traditions, critical editions, translation philosophies, and hidden biases, I was rather impressed by the claims this little document boasted. It presented ten popular English versions, mentioning the translation philosophy for each, and citing 1 Corinthians 13.4-5 from each for comparison. Though three of the translations employed vastly inferior source texts, they stood shoulder to shoulder with the others. Others injected so much bias and interpretation, that they are of little use beyond providing readers a window into the publisher’s doctrinal commitments. Sadly, this guide reduced choosing a Bible to personal taste, as if picking ingredients for a burrito. We need the facts behind Bible translations so we can prioritize manuscript fidelity over wide margins, translation accuracy over a nifty cover design, and honest transparency over the endorsement of pastor-celebrities. It’s a travesty that well-intentioned Bible purchasers end up buying what’s well-marketed rather than what is truly best.

In what follows, I intend to briefly overview the most significant issues and decisions translators make when producing English versions of the Bible. We’ll begin with the original source documents for the Old and New Testaments to gain an appreciation for the starting place of translation work. We’ll encounter several corruptions absent from the oldest manuscripts and see how our English Bibles handle them. Then we’ll explore translation methodologies and decisions made at the outset. This will put us in a good place to examine two popular versions: the King James Version (KJV) and the Message Bible (MSG), each of which illustrates important aspects of translation. Lastly, we’ll consider a few examples where doctrinal bias shapes translation. My aim in this work is to equip readers with the knowledge to understand what’s going on behind the scenes of English Bible translation so that they can not only spot and avoid problematic versions, but also read quality translations with a trained eye.

In what follows I have endeavored to remain objective and factual, though like most Christians, I have strong views on many of these issues. Sometimes I will condemn or extol a particular methodology and point out how well a translation prioritizes accuracy over sales, emotional impact, or tradition. (For the record, I am not at the time of this writing employed in the translation of any of these versions.) Furthermore, my purpose here is not to recommend the one perfect Bible as if there is such a thing. As we will see, Bible translation is a complex and challenging task and all versions have drawbacks as well as advantages. My hope is that educated Christians would increasingly make their purchasing decisions based on facts and best practices rather than marketing gimmicks and emotional reasoning. If I can accomplish this for a few, then the many hours I’ve poured into this project will be worth it.

2 The Text of the Old Testament

I want to begin our overview of the Bible translation process by looking at the manuscripts that translators use as sources. “Manuscript” is a compound word from manus “hand” and scriptio “writing.” Thus, by definition, manuscripts are handwritten documents. Consequently, we have relatively few manuscripts after 1440 when Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press invention began replacing handwritten copies. Thus, the bulk of our extant (existing) manuscripts are at least six centuries old and some of them go back more than twenty-two centuries. Furthermore, many of the most significant manuscript discoveries for both the Old and New Testaments have occurred in the last century. This sometimes makes a huge difference to Bible translation, since the source from which translators work has changed and continues to change over time. Since scholars have been putting out English translations for centuries, it’s critical for our inquiry to get a grasp of how the fields of manuscript discovery and comparison have developed over the years. But before we get into that subject let’s familiarize ourselves with a basic knowledge of what kinds of manuscripts, we have for the two major parts of the Bible—the Old Testament (OT) and the New Testament (NT)—since they are quite different.

2.1 Hebrew Manuscripts

Israelites wrote the OT (what they call the Tanakh[2]) almost entirely in Hebrew with just over one percent of it in Aramaic, a sister language.[3] The original scroll of the prophet Jeremiah or Ecclesiastes have not survived the ravages of time. Thankfully, diligent scribes copied these precious original texts, also called autographs, before they wore out, transmitting them to the next generation. Eventually, scribes began copying the entire Hebrew Bible so that each generation would have access to sacred scripture. However, most ancient manuscripts perished long ago, eventually wearing out due to age and usage. This should not surprise us very much, since even to this day, Jewish synagogues bury their scrolls when they show signs of deterioration. Nevertheless, we have two large ancient Hebrew manuscripts: Codex Leningradensis (the Leningrad Codex[4]) and כֶּתֶר אֲרָם צוֹבָא (Crown of Aleppo[5] or the Aleppo Codex). The Leningrad Codex dates to the 11th century and contains the complete OT whereas the Aleppo Codex is from the 10th century and is missing most of the Torah as well as parts of the final books.

In addition to these two, Bedouin shepherds and university archeologists competed to discover scrolls in eleven caves in Qumran near the Dead Sea between 1946 and 1956. These Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) contain 981 documents out of which about 23% turned out to be copies of the OT, mostly in Hebrew. Paleographers have dated the DSS to between 50 and 225 BC, which pushed back the date of our extant OT manuscripts more than a millennium! Even so, the DSS are not the oldest evidence of the Hebrew Bible on the planet. In 1979 archeologists discovered two small silver amulets with scripture engraved on them at Ketef Hinnom (near Jerusalem). These contain the high-priestly blessing of Numbers 6 in paleo Hebrew, dating to the 6th or 7th century before Christ. Beyond these sources, archeologists have found quite a number of other ancient Hebrew scrolls and partial remains. Here is a list of the earliest sources of the Hebrew Bible in chronological order.

| Name | Date | Scribe | Contents | Location | Available to the West[6] |

| Ketef Hinnom Silver Scroll | 6th c. bc | n/a | priestly benediction from Numbers 6 | Jerusalem | 1979 |

| Dead Sea Scrolls | 250 bc – ad 68 | various | 227 partial manuscripts (except Esther) | Jerusalem | 1947 |

| Nash Papyrus | 100 bc | n/a | Ten Commandments & Shema | Cambridge | 1902 |

| Ein-Gedi Scroll | 3rd c. | n/a | partial Leviticus | Jerusalem? | 1970 (not readable until 2016)[7] |

| Cairo Genizah Fragments[8] | 6th-8th c. | various | thousands of Bible fragments | Cambridge, Manchester, Oxford, New York | 19th c. |

| Codex Cairensis | 9th c. or 11th c. | Moses ben Asher | Prophets | Jerusalem | 1983 |

| Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus | 916 | n/a | Major Prophets | St. Petersburg | 1839 |

| London Codex (Oriental 4445) | 920-950 | n/a | Partial Torah | London | 1891 |

| Aleppo Codex | 930 | Aaron ben Moses ben Asher | Partial Torah, Prophets, Partial Writings | Jerusalem | 1958 |

| University of Michigan Torah | 950 | Ben Naftali tradition | complete Torah except Gen 1 | Ann Arbor | 1922 |

| Damascus Pentateuch | 1000 | n/a | nearly complete Torah | Jerusalem | 1975 |

| Leningrad Codex | 1010 | Samuel ben Jacob (copied from Aaron ben Moses ben Asher’s text) | Complete OT | St. Petersburg | 1863 |

| Codex Zurbil[9] | 1100 | various Samaritan scribes in paleo Hebrew | nearly complete Torah | Cambridge | 1895 |

| University of Bologna Torah Scroll | 1155 | n/a | complete Torah | Bologna | 2013 |

| Mikraot Gedolot[10] | 16th c. | Jacob ben Hayyim ibn Adonijah used ben Asher texts | complete OT | Venice | 16th c. |

In addition to these Hebrew sources for the OT, we have several important early translations in other languages, including the Greek Septuagint (3rd c. bc), the Syriac Peshitta (2nd c. ad), and the Latin Vulgate (ad 405). These ancient translations have value because the Hebrew texts they came from antedate the existing sources we have.

2.2 Hebrew Critical Text

With so many manuscripts both in Hebrew and other ancient languages, we are bound to find differences between them. Now the scribes that faithfully copied these texts did their best to prevent mistakes from creeping in, but over so many centuries, variations were inevitable. After collecting the different readings for each verse of the Hebrew Bible, specialists compare them to arrive at what they believe to be the original text. The scholars who do this work are called textual critics not because they criticize the Bible, but because they carefully analyze the differences between manuscripts to figure out the initial version. The result of textual criticism is the production of a critical text with an extensive apparatus at the bottom of the page, indicating important variant readings. This, in turn, is what translators all around the world will use to produce Bibles in modern languages.

In 1901 Rudolf Kittel began developing a critical edition of the Hebrew Bible using as a base text the Mikraot Gedolot of Jacob ben Hayyim ibn Adonijah (1470-1538), a well-known rabbinic Bible, originally printed by Daniel Bomberg in 1525. Kittel added a critical apparatus to the bottom of the page so he could print textual variants from other manuscripts such as the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Septuagint, the Vulgate, and Syriac Peshitta. He published his first edition of Biblia Hebraica in 1906 and his second edition in 1913, which corrected some mistakes in the first. In 1921 the German Bible Society of Württemberg bought the rights to Biblia Hebraica and changed out the base text to the more accurate Leningrad Codex. After revamping and expanding the apparatus under the leadership of Paul Kahle, they released the complete Biblia Hebraica in one volume in 1937. Then in the 1960s, the German Bible Society began work on the fourth edition, completely revising the textual notes in the apparatus. After nearly ten years, they published the single volume Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) in 1977. This critical edition (the BHS) underlies most translations completed between 1977 and the early 2000s.

A team of Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant scholars in thirteen countries have been working on a new version since 2004. Since this will be the fifth edition, it is called the Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ). This is a massive project with a projected output of twenty volumes with a slightly corrected main text (Leningrad) and an apparatus based on more recent discoveries as well as extensive commentary about the variants. Approximately 75% of the fascicles[11] are already available with the rest projected for completion in the near future. Since the main text merely reproduced the Leningrad Codex, translators must make their own decisions by consulting the apparatus and textual commentary. “To this day,” Philip Comfort explains,” almost all Bible scholars and translators still use the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible as the authoritative, standard text. At the same time, they make use of the findings of the Dead Sea Scrolls, as well as two other important sources: the Septuagint and the Samaritan Pentateuch.”[12] Although anyone can purchase volumes of the BHQ, they are expensive and unavailable in Bible software except for Accordance.[13] Once BHQ is complete, they will likely release a single volume Hebrew OT, which will then become the standard for Bible translators going forward. Additionally, the Society of Biblical Literature has begun developing a proper critical Hebrew text so translators won’t need to do the work of textual criticism, though they have only produced one volume so far.[14]

2.3 Redactions

The dominant Hebrew manuscripts (ben Asher texts) contain the vowels that the Masoretes inserted in the middle ages. However, since these vowels were not in the original scrolls, scholars sometimes suggest vowel changes (revocalizations) that alter the meaning of the word. This ambiguity is inherent in consonantal Hebrew texts from the Dead Sea Scrolls to today’s Jerusalem Post newspaper. Furthermore, since the Hebrew manuscripts often don’t insert blank spaces between words, readers can disagree on how to break them up. Lastly, Hebrew experts rarely suggest changes (emendations) in the consonants due to scribal errors.[15] OT translators have to decide how reliable the Leningrad text is when other Hebrew versions and early translations differ. To illustrate this, we will consider an interesting text from Proverbs 30.1 that involves both alternate word separation and revocalization. Here are the two possibilities:

| Text without the vowels or spaces | לאיתיאללאיתיאלואכל |

| Text as the Masoretes pointed it | לְאִֽיתִיאֵ֑ל לְאִ֖יתִיאֵ֣ל וְאֻכָֽל |

| Alternate spacing and revocalization | לָאִיתִי אֵל לָאִיתִי אֵל וָאֵֽכֶל |

Even without a knowledge of Hebrew the careful reader can see the overwhelming similarities between these three lines. In fact, all the consonants (the large characters) are identical, but the second and third lines differ on where to add spaces between words. Additionally, the vowels (the little markings below the consonants) differ between the second and third lines. Thus, someone reading the first line, could read it either as the second or third lines. And although these two look similar, their translation is completely different.

| to Ithiel, to Ithiel and Ucal: | NASB, NET, CSB, JPS, RA |

| I am weary, O God; I am weary, O God, and worn out. | ESV, NAB, NRSV, NIV, NLT |

In the first case, the translator interprets the Hebrew (in accordance with the Masoretic vowel pointing) as names whereas the second way of looking at it translates what the words mean.[16] The question for us is how a translation generally deals with redactions. Does it freely correct the text based on other versions and intrinsic difficulties or does it slavishly follow the Masoretic Text, no matter the consequence? Fortunately for us, translations these days tend to add footnotes when significant textual variants are possible for a given verse. Although this is an important aspect of translation, it happens rarely so I don’t want to dwell on it longer than we need to.

Now, I realize this was a lot of detailed information, but it is important to understand where scholarship is at for the text of the OT. I would have thought that scholars had established the text of the OT centuries ago and that there was little new to discuss. However, what I’ve discovered is that not only is the Hebrew text in the process of a massive revision, but many translations do not take into account the amazing manuscript discoveries that occurred in the twentieth century (see table above). This means that we have good news and bad news. The bad news is that some of our most beloved and traditional Bibles do not reflect the earliest and best Hebrew texts. Nevertheless, the good news is that we are moving closer and closer to the original year by year. I realize how counterintuitive this seems. One would think Bomberg’s printed Hebrew Bible from 500 years ago would be more accurate than the 1977 BHS. However, in the twenty-first century we have better access to both many more and much older manuscripts, especially due to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. This means that newer Bibles are getting progressively more accurate in reflecting the older Hebrew texts (assuming the translation is accurate).

Even if this all seems rather startling, the situation is not nearly as alarming as it could be. Since Hebrew scribes, especially the Masoretes, had toiled assiduously to pass on the scriptures as accurately as possible, the differences between these texts tend to be quite minor. To my knowledge, no biblical doctrine is at risk of getting overturned due to manuscript variations. Now that we’ve briefly considered the manuscript situation for the OT, let’s turn our attention to the NT.

3 The Text of the New Testament

Christianity has been missionary minded from the beginning. Jesus was an itinerant preacher who travelled about spreading the gospel of the kingdom and calling his countrymen to repentance. It should not surprise us that his early followers committed much to writing for the purpose of spreading the good news far and wide. Of course, this necessitated a prodigious amount of copying to get the message out to as many as possible. Over the years, Christianity made its way across the Roman empire to Asia, Africa, and eventually the Americas and Australia. As we would expect, most of the manuscripts Christian scribes made have long ago fallen to pieces. However, more than five thousand have survived to our own day. Sadly, most of them do not contain the entire NT.

3.1 Greek Manuscripts

The oldest NT manuscripts come to us on papyrus, an ancient form of paper made from a reed plant that grew along the banks of the Nile River in Egypt. After laying them out crosswise and pressing them together, ancient scribes wrote on them. Although this material could not survive very long in wet climates, papyri can remain in good condition for millennia in the right conditions. So far archeologists and textual critics have catalogued around 130 NT papyri. “These manuscripts,” Philip Comfort notes, “provide the earliest direct witness to the New Testament autographs.”[17] Here are a few of them.

| Papyrus # | Date | Contents | Location | Available |

| P45 | 3rd c. | Gospels, Acts | Chester Beatty Library, Dublin | 1933 |

| P46 | 2nd/3rd c. | Romans, Hebrews, 1 Corinthians – 1 Thessalonians | Chester Beatty Library, Dublin | 1930 |

| P52 | 2nd c. | John 18.31-33, 37-38 | University Library, Manchester | 1934 |

| P64 | 2nd/3rd c. | Matthew (partial) | Magdalen College, Oxford | 1901 |

| P75 | 3rd c. | Gospels | Vatican Library, Rome | 1950s |

| P98 | 2nd c. | Revelation 1.13-20 | French Institute for Oriental Archeology, Cairo | 1971 |

| P104 | 2nd c. | Matthew 21.34-37, 43, 45 | Sackler Library, Oxford | 1997 |

These papyri, designated by P followed by a superscript, occupy the first place of importance for NT manuscripts, since they are so close to the time of the writing of the NT. However, since they only contain fragments of the NT, we depend on later manuscripts as well. In the second category, we have 323 uncials, which are manuscripts written on parchment or vellum (animal skins) in majuscule (capital) letters. These survived better than the papyri, even in wet climates. Scholars reference them with a numbering system, always starting with a 0. Additionally, the more famous codices have a letter associated with them. Here are a few noteworthy examples.

| Manuscript | Name | Date | Contents | Location | Available | Family |

| Codex Sinaiticus | 01 (א) | 4th c. | Old Testament, New Testament, Epistle of Barnabas, Shepherd of Hermas | British Library, London | 1844 | Alexandrian |

| Codex Alexandrinus | 02 (A) | 5th c. | Old Testament, New Testament, Epistles of Clement | British Library, London | 1621 | Byzantine & Alexandrian |

| Codex Vaticanus | 03 (B) | 4th c. | Matthew – 2 Thessalonians, Hebrews 1-9, James – Jude | Vatican Library, Rome | 15th c. | Alexandrian |

| Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus | 04 (C) | 5th c. | Gospels, Acts, Paul’s Epistles, Revelation | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | 1453 | mixed |

| Codex Bezae | 05 (D) | 5th c. | Gospels, Acts | University Library, Cambridge | 9th c. | Western |

In addition to these majuscules, we have another nearly 3,000 minuscule (lowercase) manuscripts, each designated by a regular number. This writing style came into use from the 9th and 10th centuries onward. Here are a few examples:

| # | Date | Contents | Location | Available |

| 1 | 12th c. | New Testament except Revelation | Basel University Library, Basel | 15th |

| 2 | 11th/12th c. | Gospels | Basel University Library, Basel | n/a |

| 3 | 12th c. | Gospels, Acts, Paul’s Epistles, General Epistles | Austrian National Library, Vienna | 14th |

| 33 | 9th c. | Gospels, Acts, Paul’s Epistles, General Epistles | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | 19th |

| 2017 | 15th c. | Revelation | Saxon State Library, Dresden | n/a |

Lastly, approximately 2,500 lectionaries have survived, designated by a cursive ℓ followed by a number. These are liturgies—scriptures arranged in the order that lectors would read them out publicly as part of worship (1 Timothy 4.13). They include both majuscule and minuscule text types. Here are some examples of the lectionaries.

| # | Origin | Contents | Location | Available |

| ℓ59 | 12th c. | Acts | State Historical Museum, Moscow | 1655 |

| ℓ60 | 11th c. | Gospels, Acts | Bibliothèque nationale de France | 19th |

| ℓ253 | 11th c. | Gospels | Russian National Library, Saint Petersburg | 19th |

| ℓ259 | 13th c. | Acts, Paul’s Epistles | Bodleian Library, Oxford | 1883 |

| ℓ890 | 15th c. | Gospels | Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai | n/a |

| ℓ1977 | 12th c. | Gospels, Acts | National Library, Ohrid, Macedonia | n/a |

Adding the papyri, majuscules, minuscules, and lectionaries together, we have around 5,900 Greek manuscripts of the NT today. Although these manuscripts are locked away in museums all around the world, the dawn of the digital has provided new opportunities to access them online. However, it’s important to keep in mind that this is a moving number. Some manuscripts perish in war and through natural disaster while new ones come to light. Of particular interest is the excellent work that the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM) has accomplished under Daniel Wallace’s leadership. Since 2002, they have travelled the world taking thousands of high-quality digital pictures of ancient manuscripts to post online for free access.[18] Needless to say, NT textual scholars have a wealth of material to access and analyze. For the sake of brevity, I have not included physical remains like the thirty amulets with varying portions of scripture engraved on them, dating from the third to fourteenth centuries. We will also not cover the thousands of early translations from Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, and Ethiopic.[19]

3.2 Greek Critical Text

The work of comparing Greek manuscripts to arrive at a complete text began in 1502 when a team of Roman Catholic specialists led by Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros gained access to several medieval manuscripts.[20] After more than a decade, they produced the Complutensian Polyglot Bible and it included both Old and New Testaments in six volumes with multiple languages in parallel columns.[21] Although Cisneros had completed and printed the NT in 1514, he delayed until 1517 when the whole Bible was finished to distribute it. However, in the meanwhile, a wily priest-scholar named Desiderius Erasmus, rushed his own Greek New Testament (GNT) to print in 1516 after successfully securing the pope’s approval for exclusive publishing rights for a four-year period. This delayed the Complutensian Polyglot’s publication until 1520, though it was not widely available until 1522. This deft maneuver insured Erasmus’ place in history as the first one to publish and distribute a Greek New Testament on the printing press. However, because he rushed the work, his version contained many typos, transcription mistakes, and other errors that he corrected in subsequent editions in 1519, 1522, 1527, and 1535. Sadly, Erasmus’ versions derived from just a few late manuscripts from the twelfth century (including minuscules 1 and 2)[22] as Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman explain:

Since Erasmus could not find a manuscript that contained the entire Greek Testament, he utilized several for various parts of the New Testament. For most of the text he relied on two rather inferior manuscripts from a monastic library at Basle, one of the Gospels and one of the Acts and Epistles, both dating from about the twelfth century. Erasmus compared them with two or three others of the same books and entered occasional corrections for the printer in the margins or between the lines of the Greek script. For the Book of Revelation, he had but one manuscript, dating from the twelfth century, which he had borrowed from his friend Reuchlin. Unfortunately, this manuscript lacked the final leaf, which contained the last six verses of the book. Instead of delaying publication of his edition while trying to locate another copy of Revelation in Greek, Erasmus (perhaps at the urging of his printer) depended on the Latin Vulgate and translated the missing verses into Greek.[23]

This wasn’t an isolated incident as Hannibal Hamlin and Norman Jones point out: “Erasmus translated passages back from the Latin into Greek…in many other instances whenever he mistrusted the Greek sources.”[24] Even though Erasmus’ GNT had these flaws, it provided eager translators like Martin Luther an accessible GNT to make his German translation of 1522 and William Tyndale to put out his English version in 1526.

Next, Robert Estienne (aka Roberto Stephanus), a printer and classical scholar, began putting out editions of the GNT in 1528 and 1546. These were noteworthy for their quality and beautiful typeface, designed by Claude Garamond. His 1550 edition was the most significant and became known as the Editio Regia (Royal Edition) and the Textus Receptus (Received Text).[25] Estienne combined both the Complutensian Polyglot and Erasmus’ version along with fourteen other manuscript sources. Furthermore, his version was the first to include a critical apparatus (i.e. footnotes), wherein he placed variant readings, as well as verse numbers.[26] His masterpiece quickly became the dominant critical text used by translators in Europe, holding sway until 1880. Most of his sources were late minuscules, though he also used Codex Bezae (5th c.) and Codex Regius (8th c.). Even though Estienne’s text was a huge leap forward, it did not take into account the papyri or any of the majuscules (apart from Bezae and Regius), since they were either undiscovered or inaccessible to the Europeans doing this work. Unfortunately, this Textus Receptus version of the GNT grew in popularity to such a degree that subsequent attempts to improve it based on earlier manuscripts sometimes fell on deaf ears.

For the next two centuries after the 1550 Textus Receptus came out, scholars “ransacked libraries and museums, in Europe as well as the Near East, for witnesses to the text of the New Testament.”[27] Then in the late 18th century, Johann Griesbach boldly parted from the Textus Receptus and arrived at a better Greek critical text by applying a list of objective criteria to the manuscripts available to him.[28] Next, in the mid-19th century, Lobegott Friedrich Constantin von Tischendorf dedicated his life to locating and publishing early NT manuscripts. He worked on a number of texts in the Bibliothèque Nationale (National Library) at Paris, including Codex Ephraemi. Then, in 1844 he visited St. Catherine’s monastery next to Mount Sinai and noticed some manuscripts in a wastebasket that the monks were using to start fires. Tischendorf immediately recognized the antiquity and good condition of the Greek OT manuscripts and convinced them to allow him to take 43 leaves with him. On subsequent visits, he discovered Codex Sinaiticus, arguably the oldest complete GNT on the planet, and negotiated for them to allow him to present it as a gift to the Russian Czar so that scholars could access it. Later, in 1933, the Soviet Government sold it to the British Museum where it now resides, though these days one can readily access the digital version online.[29]

Then in 1881, Brooke Westcott and Fenton Hort, working from the many discoveries found since Estienne’s Textus Receptus, built upon the work of Griesbach to produce a “truly epoch making” critical text that was “doubtless the oldest and purest text that could be attained on the basis of information available.”[30] They produced two volumes: the first their reconstruction of the GNT and the second an explanation of the principles they followed to make decisions between alternate readings. Their methodology came to dominate the field for the next century. Next came Eberhard Nestle who continued the efforts of Westcott and Hort to produce a widely used pocket GNT for the Württemberg Bible Institute in Stuttgart, Germany in 1898. This GNT went through many important subsequent editions. Nestle’s son, Erwin, took over the revisions with the thirteenth edition in 1927, continuing his father’s work. In 1963 Kurt Aland came on board and expanded the work to include many additional manuscripts in the critical apparatus for the 25th edition. Since new manuscripts kept coming to light, this work has persisted to our own day, culminating in the 28th edition, published by the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (Germany Bible Society) in 2012.[31] This Greek critical text of the NT (The Nestle-Aland 28th edition) is what most translators use as a source for our English NTs, though work is underway to produce several new Greek critical texts.[32]

As with the OT, so with the NT, the pursuit of manuscripts along with the development of textual criticism over the last couple of centuries has worked wonders in improving our access to earlier and less corrupt forms of the GNT. Thus, someone studying a recent critical GNT today encounters a text more accurate than someone reading from a manuscript a millennium ago. Now, I cannot deny that this seems paradoxical, since someone living so long ago was so much closer to the time when the NT came into existence. However, our critical texts go back to manuscripts from the fourth, third, and even the second centuries, making them older and better. This makes sense when we consider that corruptions tend to increase with time as generations of Christian copyists produce new handwritten GNTs. Even so, thanks to the work of textual scholars over the last century and a half, we are confident about the great majority of textual variants with only a small percentage that are up for debate. To be specific, the NA28 GNT has 7,941 verses in it and the committee of textual scholars only had difficulty determining 378 variants.[33] This means that the text of the GNT is 95.2% certain with only 4.8% up for discussion. Even so, many of the readings in the 4.8% do not significantly alter exegesis, much less doctrinal considerations. This doesn’t mean the differences aren’t important, but it does mean that we don’t need to doubt the NT teaching on salvation matters like the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. We will return to listing out a handful of the most significant differences shortly, but first, let’s turn our focus to the subject of translation.

4 Translation Approaches

Translators aim to accurately convey a source document into a receptor language. However, since no two languages precisely line up with each other, translation involves more than merely substituting a word in biblical languages for one in the translation language. Translators need to add and remove words as well as rearrange them. Rather than describing this process, let’s consider an example from 1 Timothy 2.5 as an illustration of the process.

| NA28 | Εἷς γὰρ θεός, εἷς καὶ μεσίτης θεοῦ καὶ ἀνθρώπων, ἄνθρωπος Χριστὸς Ἰησοῦς |

| Exact | one for God, one and mediator of God and men, man Christ Jesus |

| Finished | For (there is) one God, and (there is) one mediator of God and mankind, (the) man Christ Jesus |

In this example, the first line is Greek from the Nestle-Aland 28th edition (NA28), the second, an exact English equivalence, and the third, a proper English translation. Notice how the word “for” (γὰρ) is second in the Greek but comes first in English. This is because γάρ (gar) is a postpositive—a Greek word that always appears after the word it acts upon. Also, I added in quite a few extra words to make good English, including inserting “there is” twice. This is because the Greek language does not always supply the verb “to be” when it is implied (nor does Hebrew). Then I added in the word “the” (the definite article) before “man Christ Jesus.” I had to do this, because Greek diverges from English convention by not including the definite article, ὁ (ho), when it’s clear the phrase is already definite. Lastly, I changed “men” to “mankind” since both sexes are in view, not just men. This is just one simple sentence in Greek, and we’ve already encountered four differences that English translators would account for in order to functionally render the source language into the target language. With this in mind, we are in a good place to consider the two major translation philosophies: formal equivalence and dynamic equivalence.

4.1 Formal Equivalence (Word for Word)

Formal equivalence translations do their best to stick to the form and exact meaning of the original text, using a literal “word for word” approach as much as possible. Now, since the Hebrew and Greek languages have different conventions for word order than English, a more literal translation can sound awkward or obscure in English. Nevertheless, formal equivalence translators would rather sacrifice readability for accuracy. They want to give the reader a translation that is as transparent as possible to the words, phrases, and style of the original. Gordon Fee explains: “If the Greek or Hebrew text uses an infinitive, the English translation will use an infinitive. When the Greek or Hebrew has a prepositional phrase, so will the English…The goal of this translational theory is formal correspondence as much as possible.”[34] Some formal equivalence translations even make a point to signal the reader with italics whenever they add in English words to smooth out the reading. The end result empowers readers to interpret scripture for themselves. Ron Rhodes writes:

Formal equivalence translations can also be trusted not to mix too much commentary in with the text derived from the original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. To clarify, while all translation entails some interpretation, formal equivalence translations keep to a minimum in intermingling interpretive additives into the text. As one scholar put it, “An essentially literal translation operates on the premise that a translator is a steward of what someone else has written, not an editor and exegete who needs to explain or correct what someone else has written.”[35]

Over and over the formal equivalence approach transfers the decision to the reader to figure out what the text means. Thus, if the original contains ambiguities, the translator seeks to preserve them so that the reader has the same interpretive options as the original audience. Several English translations that follow this tradition have the word “standard” in their name, including the New American Standard Bible (NASB), English Standard Version (ESV), and the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), among others. Now that we’ve considered the word-for-word approach, we’ll turn our attention to the thought-for-thought translation philosophy.

4.2 Dynamic Equivalence (Thought for Thought)

The twentieth century saw the beginning of a shift towards readability in English Bible translations. Early attempts of this included the Moffat New Translation (1922), the Philips New Testament (1958), and the New International Version (1978). The goal of these versions was to prioritize the sense and flow in English over replicating the style and form of the original languages. As time has passed, this way of thinking has found widespread acceptance in several bestselling translations, including the Good News Translation (1976), [36] the New Living Translation (1996), the Message Bible (2002), and the yet incomplete Passion Translation (2017, NT only). Eugene Nida who coined the term “dynamic equivalence” explains the goal as follows:

Dynamic equivalence is therefore to be defined in terms of the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptor language respond to it in substantially the same manner as the receptors in the source language. This response can never be identical, for the cultural and historical settings are too different, but there should be a high degree of equivalence of response or the translation will have failed to accomplish its purpose…[A] translation of the Bible must not only provide information which people can understand but must present the message in such a way that people can feel its relevance (the expressive element in communication) and can then respond to it in action (the imperative function).[37]

Thus, the goal is not to gain access to the words and syntax of the original, but to experience the same effect that the initial receptors would have had, keeping in mind that the original audience would not have struggled with language concerns, since they were already fluent in the source language. Once again, Rhodes helpfully summarizes the result of this process:

Dynamic equivalence translations generally use shorter words, shorter sentences, and shorter paragraphs. They use easy vocabulary and use simple substitutes for theological and cultural terminology. They often convert culturally dependent figures of speech into easy, direct statements. They seek to avoid ambiguity as well as biblical jargon in favor of a natural English style. Translators concentrate on transferring meaning rather than mere words from one language to another.[38]

The result is an easier more natural reading experience with few ambiguities. However, this is only possible because we’ve ceded to the translator(s) the hard work of figuring out what the text means. Still, champions of dynamic equivalence think this tradeoff is worth it since formal equivalence versions may require too much of readers. For example, if the Bible is difficult to understand because it is too foreign or obscure, the result is more likely to be diminished rather than improved biblical literacy. Afterall, what use is a Bible to someone if he or she gives up on reading it out of frustration or boredom? The issue of readability is even more poignant when we consider audiences like children, the unchurched, and those reading English as a second language. In the end, the question comes down to readability or autonomy. Should the Bible be easy to understand, even by non-specialists or should it transfer the work of interpretation to the reader?

4.3 Formal and Dynamic Equivalence Styles Illustrated

In order to illustrate and contrast these two philosophies, let’s consider this classic text from Genesis 9.6 about murder. (Readers may want to consult the extensive list of abbreviations in Appendix 1 for any unfamiliar translations.)

| BHS | שֹׁפֵךְ֙ דַּ֣ם הָֽאָדָ֔ם בָּֽאָדָ֖ם דָּמ֣וֹ יִשָּׁפֵ֑ךְ כִּ֚י בְּצֶ֣לֶם אֱלֹהִ֔ים עָשָׂ֖ה אֶת־הָאָדָֽם׃ |

| Literal | Pouring out the blood of the man, by man his blood will pour out because in the image of God he made the man. |

| NASB | Whoever sheds man’s blood, By man his blood shall be shed, For in the image of God He made man. |

| NLT | If anyone takes a human life, that person’s life will also be taken by human hands. For God made human beings in his own image. |

My literal translation preserves the word order of the original Hebrew, but it fails to communicate the pun between the word “blood” דָּם (dam) and “man” אָדָם (adam). Sadly, this sort of flavor routinely gets filtered out in translation. Looking at the NASB, we see its sensitivity to form in recognizing the poetic nature of this verse and rendering it as a series of lines. Furthermore, we observe that it’s English closely follows the Hebrew even though the word order is a bit awkward. For example, “By man his blood shall be shed” would work better as “His blood shall be shed by man” or, even better: “A man shall shed his blood.” Instead the NASB prioritized transparency over readability to give the reader the same form as the original. By contrast, the NLT reworks the word order and makes two additional changes: it substitutes “life” for “blood” and “human” for “man.” The NLT distances the reader from the literal Hebrew while working to communicate the overall sense. This text nicely illustrates the priorities of both translation styles.

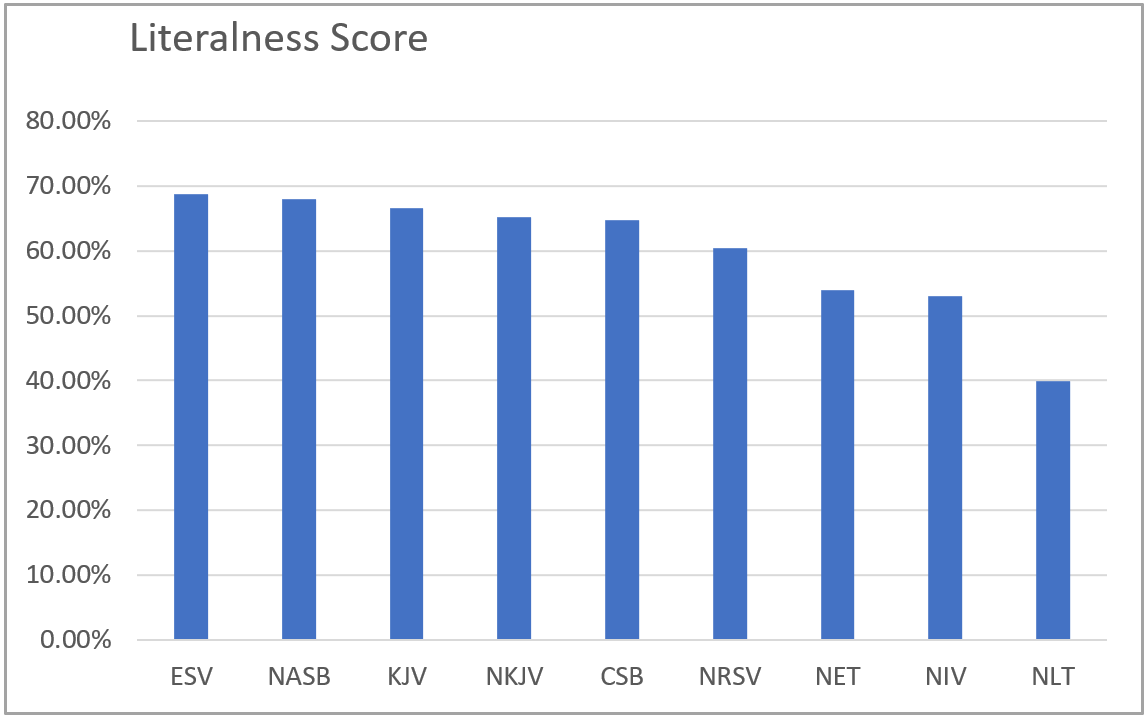

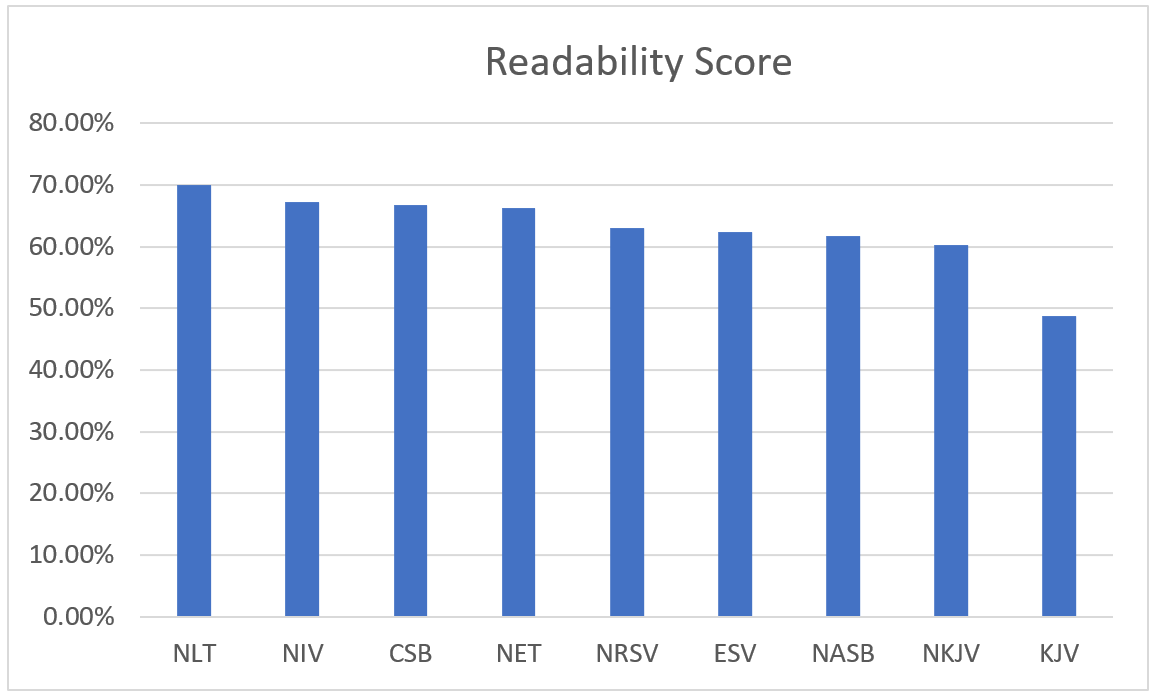

In order to see how these principles play out across translations, Bible sellers have generated graphics that show a spectrum of translations, ranked by how formal or dynamic they are. Although I’ve come across several of these, none of them indicates the criteria they use to place translations, leaving us to suspect that marketing and sales were the driving forces instead of data. What’s more, no two of these charts agree with each other in the ordering of translations. The only source I could find that even claimed to use objective criteria to rank translations was Andi Wu’s “A Quantitative Evaluation of the Christian Standard Bible.” Naturally, the main problem with this report is that it appears that Holman Bible Publishers who produce the Christian Standard Bible (CSB) sponsored the study. [39] Nevertheless, recognizing the potential for bias, we can consider the findings of Wu in the tables and graphs below.[40]

| Version | Literalness |

| ESV | 68.74% |

| NASB | 67.99% |

| KJV | 66.58% |

| NKJV | 65.21% |

| CSB | 64.83% |

| NRSV | 60.51% |

| NET | 53.94% |

| NIV | 53.10% |

| NLT | 39.90% |

| Version | Readability |

| NLT | 70.08% |

| NIV | 67.20% |

| CSB | 66.75% |

| NET | 66.28% |

| NRSV | 63.08% |

| ESV | 62.36% |

| NASB | 61.65% |

| NKJV | 60.32% |

| KJV | 48.83% |

This data shows how nine of the most popular Christian translations stack up on both literalness and readability. As we would expect, the most literal translations follow formal equivalence and the most readable employ dynamic equivalence. It’s not surprising to observe the inverse relationship between literalness and readability. This also explains a recent trend in some translations to move more toward the center. As it turns out, both translation philosophies include a wide range of styles. For example, the strictest word-for-word translation is probably Young’s Literal Translation (YLT) of 1898 where the English text so closely follows the original languages that it occasionally breaks from natural syntax, making it both highly accurate and excessively wooden.[41] On the opposite end of the formal equivalence spectrum is the CSB, which calls itself an “optimal equivalence” version since it seeks a balance between literal translation and readability. Then on the other end of thought-for-thought versions we find the Message Bible (MSG) and the Passion Translation (PT), which liberally reword whole phrases and sentences in order to prioritize the experience of the reader above all else. We will return to this issue in later sections, but for now, we need to examine several other key areas where translators make decisions.

5 Translation Decisions

My aim for this next section is to make visible many of the hidden assumptions determined at the outset when going about the work of translation. Although, most publishers can’t be bothered to inform their readers about these finer details, we can get a decent idea of their policies from the text itself. While we won’t go into detail on any of these, each issue is important to know about and can help in deciding which translation to use.

5.1 Units of Measurement

As I mentioned before the purpose of translation is to render a source document into the target language. However, does this include translating units of measurement? Translators differ on this, with some preserving the biblical units and others converting them into modern quantities. For example, the ESV translates the measurement in Numbers 28.12 as “three tenths of an ephah” whereas the Christian Standard Bible (CSB) converts the units, rendering it “six quarts.” The ephah was a standard volume measurement in Israel equivalent to roughly six gallons or twenty-three liters. Should the translation put the reader in touch with the actual units used in the Bible or should it put everything in familiar terms? Other biblical measurements include baths, cubits, minas, shekels, and talents among others.

5.2 Idioms

Every language has its own unique idioms and Hebrew is no different. For example, the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) of Amos 4.6 says, “I gave you cleanness of teeth in all your cities” whereas the NIV has, “I gave you empty stomachs in every city.” Having cleanness of teeth sounds pretty good in our modern culture, but as Robert Alter points out, it “does not have anything to do with dental hygiene but evokes a mouth in which there is no food.”[42] Still, translations are not always consistent in what idioms they translate out and which ones they pass on to the reader. For example, the NIV, which went for meaning over literalness in Amos 4.6, translates part of Psalm 60.8 as “on Edom I toss my sandal” whereas the New English Translation (NET) has “I will make Edom serve me.” Should we expect readers to do the research to understand these strange ways of talking or should they get the point while remaining blissfully ignorant of the difficulty?

5.3 Gender Inclusiveness

When the NRSV came out in 1989, it did it’s best to avoid “linguistic sexism” and the “inherent bias of the English language towards the masculine gender.”[43] The committee of translators increased the gender inclusiveness of many passages “by simple rephrasing or by introducing plural forms when this does not distort the meaning of the passage.”[44] For example, instead of the CSB’s “Let us make man in our image,” the NRSV translates it, “Let us make humankind in our image” for Genesis 1.26. A second example is the NAB on 1 Corinthians 1.26, which reads, “Consider your own calling, brothers” while the NIV has “Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called.” Should translators explicitly clarify that references to “man” or “brothers” generally include “women” and “sisters” or should that be the burden of readers? A third example is Paul’s term “inner man” (NASB) vs. “inner being” (ESV) or “inner self” (NAB) in Ephesians 3.16. If a woman is reading the Bible in the twenty-first century, will she feel excluded from this text because of male-dominated terminology? A second but related issue is whether to use masculine pronouns for God. In Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the Bible always utilizes masculine pronouns for God, however some theologians have argued that because God does not have a sexual gender, either neuter or even feminine pronouns are possible. Although God obviously transcends human gender categories, virtually all translations follow the lead of the original languages in acquiescence to God’s self-revelation as our father and preserve masculine pronouns.

5.4 Editorial Helps

Biblical manuscripts in Hebrew and Greek do not contain capitalization, chapters, verses, paragraph headings, or cross references. They have very little punctuation and sparse marginal notes. Most translations of the Bible add in chapters and verses at the traditional places and follow standard English conventions for punctuation and capitalization. Some versions capitalize pronouns that refer to God while others do not. Also, publishers, these days, tend to add in other information to aid readers. For example, much of the OT consists of poetic structures, not only in Psalms and Proverbs, but also in the prophets. Some translations will add a line and capitalize the initial word on each line to make clear to the reader what the Hebrew is doing beneath the surface. Another editorial alteration is to mark out OT quotations in the NT. Most translations do this, but how they do it differs. One translation, the NASB, capitalized the words in the NT that quoted the OT, which probably hearkened back to the typewriter era when capital letters were the only way to emphasize a text. Nowadays, however, capitalizing words and whole sentences is how we express anger through textually shouting. Some Bibles like the KJV, NKJV, NASB, and REV use italics to indicate whenever they’ve added in words for readability that were not in the source documents. (Ironically, today italic type implies emphasis, which is precisely the opposite attitude the translators want us to have about these added words.) Many add in paragraph headings that are often helpful, but sometimes steer the reader to the publisher’s theological bias. Most translations now include footnotes or marginal notes that clue the reader in to significant manuscript variants, alternate translation possibilities, cross-references, and other helpful information. Study Bibles include a running commentary on the bottom of the page with a mix of textual, doctrinal, and historical information. The NET, in particular, deserves mentioning, since it includes over 60,000 notes that clue readers in on translation issues and the reasons the committee went with the rendering they chose.[45]

5.5 Lexicography

Although it might surprise many, Robert Alter points out, “[T]he Hebrew corpus abounds in opaque words and phrases” that translators still struggle to understand.[46] “In the past century,” writes Paul Wegner, “scholars have learned a great deal about the biblical languages in the areas of grammar, syntax (the way words are related to each other), and lexicography (study of word meanings).” [47] This means that our ability to translate is improving over time, but only if translators avail themselves of the latest scholarship and lexical tools. For example, Greek Lexicons have slowly evolved from Henry Liddell, Robert Scott, and Henry Jones (LSJ) lexicon of 1843, which enjoyed several revisions, culminating in the ninth edition of 1940.[48] The next huge step forward was when Walter Bauer’s Greek-German lexicon came into English with the help of Felix Gingrich and William Arndt (BAG) in 1957. Frederick Danker got involved after Arndt’s death and subsequently published the second edition in 1979 (BAGD). The third edition came out in 2000 in which Danker took a much larger role, now known as the BDAG. However, in 2015, Brill published the Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (also called BDAG, or Brill-DAG), which brought into English the 3rd edition of Franco Montanari’s Vocabolario della Lingua Greca, the dominant Greek-Italian lexicon (an update of the LSJ). Thus, a NT translation completed in the year 1900 could not benefit from the BDAG and a translation in the year 2000 did not have access to the Brill-DAG. Over time, archeological, grammatical, and cognate studies benefit our lexical knowledge, providing newer translations increased accuracy in their understanding of the original languages. Sadly, most translations do not specify what lexical sources they used, so it can be hard to know how much they benefit from more recent scholarship.

5.6 English Vocabulary

We’ve already discussed the dilemma between formal and dynamic equivalence with the former’s preference for technical English words and latter’s preference for longer but simpler explanatory phrases. Although deciding what the meaning is and spelling it out clearly results in a more accessible translation, it simultaneously distances the reader from the actual Bible. Alter laments this when he writes:

The Bible itself does not generally exhibit the clarity to which its modern translators aspire: the Hebrew writers reveled in the proliferation of meanings, the cultivation of ambiguities, the playing of one sense of a term against another, and this richness is erased in the deceptive antiseptic clarity of the modern versions.[49]

We can observe an interesting example of this in Matthew 5.22 where the NLT has Jesus saying, “If you call someone an idiot, you are in danger of being brought before the court.” while the NAB has, “[W]hoever says to his brother, ‘Raqa,’ will be answerable to the Sanhedrin.” The two main differences here are “idiot” for “Raqa” and “court” for “Sanhedrin.” In both cases the NAB gives what the Greek says while the NLT, recognizing that people generally don’t toss around the insult “Raqa” in English, and have no idea what a Sanhedrin is, gave sanitized equivalents that are at once easier to understand and decidedly less Jewish. Other examples of cultural words include synagogue, a Sabbath day’s journey, messiah, gospel, betroth, parable, slept with his fathers, Pentecost, Passover, as well as many more. Then there are words that might mean something different in our culture than theirs, like the word δοῦλος “slave.” Because American ante-bellum slavery strongly colors how many English speakers interpret this word, some translations have opted to substitute the word “servant” for “slave.” However, servants typically have much more autonomy than either Israelite or Roman slaves. Lastly, it has become customary for translators to avoid translating certain controversial words like sheol and hades as well as some uncertain words like selah, miktam, shiggaion, abaddon, and leviathan. Each translation has to decide how to render each of these vocabulary words.

5.7 God’s Name

Most English translations follow the tradition of the Septuagint and change the nearly seven thousand instances of God’s name in the OT to “the LORD.” This obfuscation violates both translation philosophies since it neither offers the right word nor the right thought for “Yahweh”—God’s personal name. Now a few translations have bucked this trend, by translating a few usages of Yahweh (or Jehovah), including the KJV (four times), NEB (two times), and NLT (seven times).[50] Only a handful of lesser known versions consistently render יהוה as “Yahweh,” such as the NJB, LEB, and REV. One major translation, the CSB had made a name for itself by using Yahweh some 643 times in its 2009 edition, but then reversed their policy in the 2017 version, eliminating all of them in favor of “the LORD.” In their helpful Q&A document, the CSB committee lays out their reasoning for the change, including that “full consistency in rendering YHWH as ‘Yahweh’ would overwhelm the reader,” and that “feedback from readers showed that the unfamiliarity of ‘Yahweh’ was an obstacle to reading” since “they felt ‘Yahweh’ was an innovation.”[51] Even so, shouldn’t a Bible committed to accuracy, accurately translate names rather than hiding them from the reader, regardless of how this practice challenges tradition or people’s sensibilities? Of course, readers will adjust to the foreignness of God’s name as they encounter it repeatedly. Hopefully, as times goes on, courageous translation teams will increasingly favor honesty over tradition and render God’s Hebrew name into English rather than substituting “Lord”.[52]

Before looking at two specific translations—the KJV and the Message—I want to address two major additions that textual scholars know were not in the early manuscripts but find their way into virtually every version today. These are the story where Jesus rescues the adulteress woman from execution and more than half of the last chapter of Mark’s Gospel.

6 Two Enduring Corruptions

The great church historian, Jaroslav Pelikan, once wrote, “Tradition is the living faith of the dead, traditionalism is the dead faith of the living.”[53] I fear with respect to this particular issue, the latter sentiment lives on in virtually all of our English translations in two major sections of scripture where nearly all modern translations retain well-known forgeries: Mark 16.9-20 and John 7.53-8.11. Although scholars disagree whether these two passages reflect actual historical events, that neither belongs in their respective Gospels is a consensus.

6.1 The Ending of Mark (Mark 16.9-20)

We will begin with the ending of the Gospel of Mark. As it turns out, we have not two or even three different endings, but four! According to Bruce Metzger’s Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (TCGNT), here they are:

| # | Content (Quoted from ESV, Except Version 3 from TCGNT) | Mss | Year |

| 1 | 8 And they went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid. | א, B | 4th c. |

| 2 | 8 And they went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid. 9 But they reported briefly to Peter and those with him all that they had been told. And after this, Jesus himself sent out by means of them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. | L, Ψ, 083, 099, 0112, 579 | 7th c. |

| 3 | 8 And they went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid. 9 Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast out seven demons. 10 She went and told those who had been with him, as they mourned and wept. 11 But when they heard that he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it. 12 After these things he appeared in another form to two of them, as they were walking into the country. 13 And they went back and told the rest, but they did not believe them. 14 Afterward he appeared to the eleven themselves as they were reclining at table, and he rebuked them for their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they had not believed those who saw him after he had risen. 15 And they excused themselves, saying, “This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits. 16 Therefore, reveal your righteousness now” –thus they spoke to Christ. 17 And Christ replied to them, “The term of years of Satan’s power has been fulfilled, but other terrible things draw near. 18 And for those who have sinned I was handed over to death, that they may return to the truth and sin no more, 19 in order that they may inherit the spiritual and incorruptible glory of righteousness that is in heaven. | W | 5th c. |

| 4 | 8 And they went out and fled from the tomb, for trembling and astonishment had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid. 9 Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast out seven demons. 10 She went and told those who had been with him, as they mourned and wept. 11 But when they heard that he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it. 12 After these things he appeared in another form to two of them, as they were walking into the country. 13 And they went back and told the rest, but they did not believe them. 14 Afterward he appeared to the eleven themselves as they were reclining at table, and he rebuked them for their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they had not believed those who saw him after he had risen. 15 And he said to them, “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation. 16 Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned. 17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: in my name they will cast out demons; they will speak in new tongues; 18 they will pick up serpents with their hands; and if they drink any deadly poison, it will not hurt them; they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover.” 19 So then the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God. 20 And they went out and preached everywhere, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message by accompanying signs. | A, C, D, K, W, X, Δ, Θ, Π, Ψ, 099, 0112, f13, 28, 33 | 5th c. |

Each of these four versions includes Mark 16.8, but the first one ends there, whereas the others all add extra endings. The first version enjoys support from the earliest manuscripts as well as a great deal of attestation among ancient translations of Latin, Syriac, Armenian, and Georgian. The second version is very unlikely, not only because it only appears in later manuscripts, but also, because it contains “a high percentage of non-Markan words,” and “its rhetorical tone differs totally from the simple style of Mark’s Gospel,” according to Metzger.[54] The third version is only found in Codex Washingtonianus and as a partial quote in Jerome, which means its textual basis is too weak to be original. Furthermore, like the second version, it “contains several non-Markan words and expressions” resulting in “an unmistakable apocryphal flavor.”[55] The fourth version appears in the largest number of surviving manuscripts and this is no doubt, why we find it printed in nearly all of our Bibles. Even though this long version is not likely to be original to Mark, it could go back to as early as the second century (50 to 100 years after the original Mark). Once again, the vocabulary in this version diverges from Mark’s typical usage. Furthermore, verses 9-20 appear foreign to verses 1-8. For example, verse 9 suddenly changes the subject from the women in verse 8 to Jesus in verse 9. Also, verses 9-20 seem to retell the same story by introducing Mary Magdalene as if she hadn’t already come into view from verse 1. Beyond these internal considerations, only the shortest version can explain the existence of these other three. Metzger explains:

No one who had available as the conclusion of the Second Gospel the twelve verses 9-20, so rich in interesting material, would have deliberately replaced them with a few lines of a colorless and generalized summary…Thus, on the basis of good external evidence and strong internal considerations it appears that the earliest ascertainable form of the Gospel of Mark ended with 16.8. At the same time, however, out of deference to the evident antiquity of the longer ending and its importance in the textual tradition of the Gospel, the Committee decided to include verses 9-20 as part of the text, but to enclose them within double square brackets in order to indicate that they are the work of an author other than the evangelist.[56]

So, if Mark 16 originally ended in verse 8, we should ask why Mark would end his gospel with the anticlimactic words, “they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” The NET Bible footnote helpfully lays out the options:

There are three possible explanations for Mark ending at 16:8: (1) The author intentionally ended the Gospel here in an open-ended fashion; (2) the Gospel was never finished; or (3) the last leaf of the ms [manuscript] was lost prior to copying. This first explanation is the most likely due to several factors, including (a) the probability that the Gospel was originally written on a scroll rather than a codex (only on a codex would the last leaf get lost prior to copying); (b) the unlikelihood of the ms not being completed; and (c) the literary power of ending the Gospel so abruptly that the readers are now drawn into the story itself…The readers must now ask themselves, “What will I do with Jesus? If I do not accept him in his suffering, I will not see him in his glory.”[57]

If textual critics and translators believe that Mark 16 originally ended in verse 8, why do nearly all Bibles add in the forged verses 9-20? The NET, which fully acknowledges that verses 9-20 were “most likely…not part of the original text of the Gospel of Mark,” still included them even if they employed a smaller font-size and enclosed the section in double brackets. We will return to this question after we consider our second major forgery that most Bibles keep printing: John 7.53-8.11.

6.2 The Adulteress Woman (John 7.53-8.11)

Here is the text in full:

John 7.52-8.13 (Quoted from NIV)

52 They replied, “Are you from Galilee, too? Look into it, and you will find that a prophet does not come out of Galilee.” [ 53 Then they all went home, 1 but Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. 2 At dawn he appeared again in the temple courts, where all the people gathered around him, and he sat down to teach them. 3 The teachers of the law and the Pharisees brought in a woman caught in adultery. They made her stand before the group 4 and said to Jesus, “Teacher, this woman was caught in the act of adultery. 5 In the Law Moses commanded us to stone such women. Now what do you say?” 6 They were using this question as a trap, in order to have a basis for accusing him. But Jesus bent down and started to write on the ground with his finger. 7 When they kept on questioning him, he straightened up and said to them, “Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.” 8 Again he stooped down and wrote on the ground. 9 At this, those who heard began to go away one at a time, the older ones first, until only Jesus was left, with the woman still standing there. 10 Jesus straightened up and asked her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” 11 “No one, sir,” she said. “Then neither do I condemn you,” Jesus declared. “Go now and leave your life of sin.” ] 12 When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.”

Although this incident is beloved by readers, preachers, and moviemakers alike, it is missing from a staggering number of early manuscripts, including P66, P75, א, B, L, N, T, W, X, Y, Δ, Θ, Ψ, 0141, 0211, 22, 33, 124, 157, etc. Early translations including the oldest Syriac, Sahidic, Bohairic, and some Georgian, Armenian, and Gothic manuscripts do not include it. Not a single Christian author comments upon this text before Euthymius Zigabenus in the twelfth century.[58] Furthermore, when this passage occurs in the manuscripts, it floats around. In most, it appears after John 7.52 (E, F, G, H, K, M, U, Γ, Π, 28, 700, 892, etc.), however in manuscript 225, it is after 7.36. In several Georgian translations, it’s after 7.44; in yet other manuscripts it’s after 21.25 (1, 565, 1076, 1570, 1582); and in one manuscript we find it in Luke 21.38 (f13).[59] The fact that this passage floats around in different parts of John and Luke is evidence that scribes didn’t quite know where to put it.

Internal evidence also supports omission. Not only is the text replete with vocabulary uncharacteristic of John, but it interrupts the flow of the text. For all of these reasons, Metzger writes, “the case against its being of Johannine authorship appears to be conclusive…It is obviously a piece of oral tradition which circulated in certain parts of the Western church and which was subsequently incorporated into various manuscripts at various places.”[60] But, if scholars agree John 7.53-8.11 is not part of John, then why does virtually every Bible continue to include it? Daniel Wallace explains the situation nicely:

[E]ven though most translators would probably deny John 7.53–8.11 a place in the canon, virtually every translation of the Bible has this text in its traditional location. There is, of course, a marginal note in modern translations that says something like, “Most ancient authorities lack these verses.” But such a weak and ambiguous statement is generally ignored by readers of Holy Writ. (It’s ambiguous because many readers might assume that in spite of the ‘ancient authorities’ that lack the passage, the translators felt it must be authentic.)

How, then, has this passage made it into modern translations? In a word, there has been a longstanding tradition of timidity among translators. One twentieth-century Bible relegated the passage to the footnotes, but when the sales were rather lackluster, it again found its place in John’s Gospel. Even the NET Bible…for which I am the senior New Testament editor, has put the text in its traditional place. But the NET Bible also has a lengthy footnote, explaining the textual complications and doubts about its authenticity. And the font size is smaller than normal so that it will be harder to read from the pulpit! But we nevertheless made the same concession that other translators have about this text by leaving it in situ.[61]

So, this text is a forgery. It’s not part of the Gospel of John. More or less, everyone knows this, and still the committees that make the final decisions in translations insist on keeping it. Wallace hints at the reason: money. We do well to remember that there’s an inescapable financial component to publishing Bible translations. In the wake of so many “King James Only” advocates, it’s hard enough to sell Bibles in certain parts of America without removing this beloved story about a forgiven adulteress woman. What I find so amazing about Wallace’s admission above is not that he blames sales or that he nails translators for “a longstanding tradition of timidity,” but that despite all of his certainty and clout as the senior New Testament editor, he still couldn’t excise this addition from his own translation. This is bad news, not only for the NET, but for all Bible translations that meekly submit to traditionalism over against the historical facts of the matter.

Furthermore, these two texts—Mark 16.9-20 and John 7.53-8.11—are ripe for exposure by a hostile atheist. In fact, I knew one young man who lost faith in scripture once a secular professor assaulted its credibility on the grounds that it contained these two forgeries. When outspoken critic, Bart Ehrman, published his Misquoting Jesus, many more became aware of this silent sin. After this book came out in 2009 and sales skyrocketed to The New York Times best seller list, Wallace said:

I wrote a critique of Ehrman’s book that was published in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. There I said, “keeping [John 7:53–8:11 and Mark 16:9–20] in our Bibles rather than relegating them to the footnotes seems to have been a bomb just waiting to explode. All Ehrman did was to light the fuse. One lesson we must learn from Misquoting Jesus is that those in ministry need to close the gap between the church and the academy. We have to educate believers. Instead of trying to isolate laypeople from critical scholarship, we need to insulate them. They need to be ready for the barrage, because it is coming. The intentional dumbing down of the church for the sake of filling more pews will ultimately lead to defection from Christ. Ehrman is to be thanked for giving us a wake-up call.

Even so, nearly all translations today stubbornly continue to include both of these texts. Maybe they assuage their consciences by telling themselves, “At least we told the truth in the footnote” or, “At least we put it in brackets,” or, “At least we put it in a smaller font.” This simply will not do anymore. It’s time to tell the truth. It’s time to relegate these two leftovers from the Textus Receptus to the footnotes and let the chips fall where they may.

7 The King James Version

Now, I want to turn our attention to two specific translations: the King James Version and the Message in order to address some unique issues related to each. These two versions occupy the fringes of the spectrum in Bible translation. The King James Version is excessively literal, even to the point of inverting sentences to mimic Hebrew and Greek grammar. The Message is so flowing that it often reworks verses so much that they are unrecognizable to avid Bible students. First, we will begin with the KJV and then we’ll move on to analyze the Message.

Notwithstanding earlier attempts to bring the Bible into English by Bede (8th c.), John Wycliffe (14th c.), and others, the story of the KJV really begins with William Tyndale’s Bible. He completed the NT in 1526, using Erasmus’ printed Greek text.[62] After this, he began work on the OT, but only finished about half of it when the English king’s cronies burned him at the stake in 1536. To say Tyndale was a brilliant linguist would be an understatement. He could operate in English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. His translating skills have deeply impacted English language and literature to this day. For example, he coined words and phrases that we still use today like “atonement,” “my brother’s keeper,” “the powers that be,” “Passover,” and “scapegoat.” Tyndale dedicated his life to putting the Bible into the language of ordinary people so that even a ploughboy could read it. Although he was unable to finish the task, his dying words were, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” [63] The answer to that prayer came in the person of Miles Coverdale who took up Tyndale’s cause and published the first complete English Bible in 1535. According to F. F. Bruce, Coverdale’s Bible was “basically Tyndale’s version revised in the light of the German versions, and not noticeably improved thereby.”[64] This led to a quick succession of revisions, including the Matthew Bible (1537), the Great Bible (1539), the Geneva Bible (1560), and the Bishop’s Bible (1568).

In 1605 King James authorized a revision of the Great Bible and the Bishop’s Bible to compete with the popular Geneva Bible. Unlike the Geneva Bible, which James called “very partiall, untrue, seditious, and savouring too much of dangerous and traytorous conceits [sic],”[65] this new “Authorized Version” would not have any marginal notes, least of all those undermining his kingly authority. The king appointed fifty-four translators who, Paul Wegner notes, “were the leading classical and Oriental scholars in England at the time, both traditional Anglican and Puritan.”[66] Even so, for much of the NT, the KJV simply revised Tyndale’s 1534 edition. “The makers of the Authorised [sic] Version,” writes David Daniell, “who did some curious things elsewhere, had the wisdom to pass on Tyndale’s New Testament as they had received it. Phrase after phrase after phrase is his.”[67] Even though subsequent analysis of the KJV has overwhelmingly praised it as a magnificent accomplishment, like all new translations, it faced harsh criticism in its own time. Luther Weigle explains:

For eighty years after its publication in 1611, the King James version endured bitter attacks. It was denounced as theologically unsound and ecclesiastically biased, as truckling to the king and unduly deferring to his belief in witchcraft, as untrue to the Hebrew text and relying too much on the Septuagint. The personal integrity of the translators was impugned. Among other things, they were accused of “blasphemy,” “most damnable corruptions,” “intolerable deceit,” and “vile imposture.”…But the attacks were negligible. The King James version quickly displaced the Bishop’s Bible as the version read in the churches.[68]